Living with Dissociative Identity Disorder can be excruciatingly lonely. I endured my loneliest moments with DID in the first few years after diagnosis. Granted, my primary relationship at the time was drawing its dramatic last breaths and I'd recently lost my job. I had virtually no support system and was barely able to feed myself and my child. There's no doubt my loneliness was the result of more than just my Dissociative Identity Disorder diagnosis. But when I look back through my diaries from that time period, it's clear the diagnosis was partially to blame. In hindsight, it's easy to see why.

DID Diagnosis

Prior to my Dissociative Identity Disorder diagnosis my alters existed and operated outside of my awareness. They affected my life in ways I had no explanation for, like invisible strangers living in your house and rearranging the furniture. Receiving the diagnosis was like someone turned on a light and exposed the multitude around me. Suddenly I could see and hear what had always been there. None of what occurred in the aftermath of that diagnosis was new. But all of it was severely amplified. And I felt, among other things, fear.

The first couple of years after my Dissociative Identity Disorder diagnosis are heavily documented in my diaries. The entries tell a disturbing and, I now know, common tale. I wish I'd known that what I was experiencing, as unhinged as it made me feel, was normal for people newly diagnosed with DID. With that in mind, I've decided that rather than just tell you what the aftermath of that diagnosis was like for me, I'll open up my diaries and show you.

I was sitting in a group therapy session once when the leader succinctly described the perception those of us with multiple personalities have of ourselves as groups of entirely separate people by writing the following on the white board: Me/Not Me. This is me. That is not me. For instance, I am a writer. But if another member of my system were assigned the task of writing this blog post, we would see how the Multiple Personality Disorder label came about. Some might have done a passable job. Others would have struggled mightily only to ultimately produce a choppy, thoroughly unimpressive piece of work. I am me. They are not me.

Yesterday I talked about the Dissociative Identity Disorder diagnosis and the vital role clinicians play in making that diagnosis. One of the reasons it's important to talk to a therapist if you think you may have DID is that dissociation by nature impedes awareness. Most people can't see the spot between their shoulder blades without a mirror. Similarly, most severely dissociative people aren't able to clearly recognize the symptoms of DID and the extent of their problem without the help of a skilled clinician. In fact, the diagnosis often comes as a shock. Today I'd like to share with you a typical diagnosis story - my own.

We were talking about dissociation when a man I once knew told me he'd been entirely unaware of a hospital stay until he got the bill. I didn't say it, but I immediately thought, 'he obviously has Dissociative Identity Disorder.' I now know how presumptuous that was. Though his experience was clearly indicative of something outside of everyday experience, it's taking a lot for granted to assume that something is DID. And looking back, it's absurd that I was so convinced. Not satisfied with a second opinion of my own diagnosis, I sought out four. One would think someone as hesitant to jump to conclusions as that would exercise a little more caution.

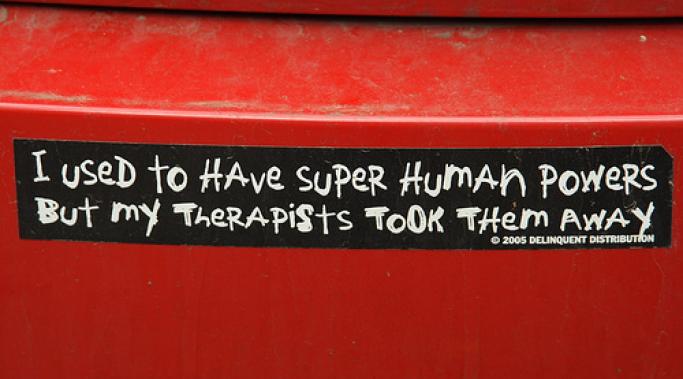

Among those with Dissociative Identity Disorder, there's some debate about whether it should be called a disorder at all. Some even view DID as evidence of mental health. When you consider that its development is regarded as an example of adaptive functioning by many of both those who live with it and those who treat it, it's easy to understand why some might dispute the mental illness label. Mental illness by definition implies maladaptive functioning - it interferes with and disrupts daily living. But Dissociative Identity Disorder is often described as life-saving. Which is it?

One of the obstacles I encountered in coming to terms with my dissociative identity disorder (DID) diagnosis was the idea that DID is by and large caused by horrendous abuse. Because DID and unimaginable trauma were intrinsically linked in my mind, I thought accepting my diagnosis required believing that I had suffered inconceivable horrors, repressed memories of child abuse that were lurking somewhere in the recesses of my dissociative mind. I didn't want to believe that, so I rejected the diagnosis altogether. I wish I'd known that tolerating ambiguity is part of dissociative living, and that it's possible to reconcile yourself to having DID without making assumptions about your history.