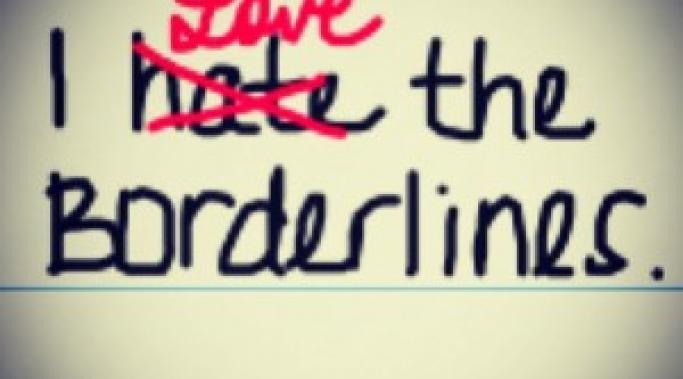

The new movie, Welcome to Me, definitely offers an offensive depiction of borderline. Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is a complex and challenging illness for those with expertise; so I wasn't entirely surprised that Welcome to Me failed miserably in representing BPD. If my sentiment wasn't already clear, I hated this film. The TV caricature with a borderline label contained traits uncharacteristic of BPD. The movie, Welcome to Me, is offensive and reckless; this movie transmits misinformation to the public, further stigmatizing borderline personality disorder.

More than Borderline

For me, the most helpful framework in understanding borderline personality disorder (BPD) comes out of schema therapy, a borderline personality disorder treatment, which includes a concept known as schema modes. The easiest way to understand schema modes is to think of them as personalities. Different personalities take over to protect the borderline when she is hurt or threatened in some way. Schema modes in borderline personality disorder are a form of maladaptive coping that the person learned in response to childhood trauma, and schema therapy is designed to address these modes.

As a person with borderline personality disorder (BPD), I sit here with law school deadlines looming and find myself writing instead about procrastination. Might there be a relationship between borderline personality disorder and procrastination?

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is complex and challenging--for both patients and their doctors (among other clinicians). As patients suffering at BPD's mercy, however, sometimes we forget that doctors of borderline personality disorder are human and deserve sympathy, too.

Borderline personality disorder (BPD) is widely underdiagnosed. However, the problem is not just a matter of healthcare access, as even BPD individuals who seek treatment are misdiagnosed. The problem runs deeper in the packaging and distribution of knowledge among professionals. The majority of mental healthcare providers hold misconceptions about BPD, and even those who don’t seem to perpetuate myths around borderline personality disorder.

BDSM and alternative sex have been hot topics in the wake of 50 Shades of Grey. Joining the terms B & D (bondage and discipline), D/S (domination and submission), and S & M (sadism and masochism), BDSM describes a wide variety of erotic practices and alternative sex. Proponents of BDSM say that mutual consent distinguishes it from crimes such as sexual assault and domestic violence. Not only is BDSM not pathological, they say, but it can even be healthy, therapeutic, and rewarding. The issue is far too complex to discuss in its entirety here, so I wish to make only a couple narrow points, especially as they pertain to alternative sex, BDSM and people with borderline personality disorder (BPD).

I asked my Facebook friends what they wanted to know about borderline personality disorder (BPD). Someone asked:

"I'd like to know how does one discover or come to terms with being BPD? It took me years to learn of my depression, and I would assume one doesn't always know they have BPD - so how do they find out? And once they find out, then what?"

I’m very open about my condition. I even write about it on Facebook and volunteer information in class. And I like calling myself “a borderline.” The peculiar self-reference is deliberate. For a while I subscribed to the idea that we are not our diseases—we are not borderline, we have borderline—and to be fair, I still do; however, I also think there’s power in language and have decided to reclaim "borderline" to reduce stigma.

Hi, my name is Mary Hofert Flaherty. I was born and raised in a Chicago suburb and moved to Hawaii six years ago where I am currently studying law. Prior to Hawaii, I lived in a conservative area of Michigan where I started college at 18. It was there, during my first year, that I became severely depressed and sought professional, psychiatric help. Unfortunately, it took eight years of regular therapy and psychiatric care from an assortment of professionals in three states—including an inpatient admission following a suicide attempt—to find the correct diagnosis of borderline personality disorder.

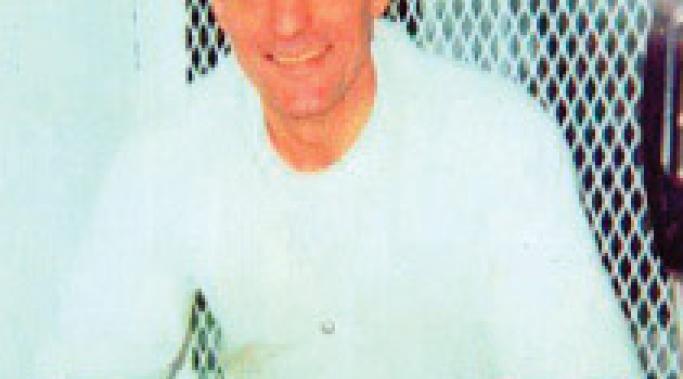

Navy veteran, Scott Panetti, was diagnosed with schizophrenia in 1978 and hospitalized 14 times for the disorder. In 1992, he suffered a psychotic break and killed his wife's parents, telling the police that "Sarge" did it and demons were laughing at him. Amazingly, he was allowed to represent himself, and passed up a plea deal that would have saved his life. At his trial, he wore a cowboy suit, subpoenaed Jesus Christ, the Pope and President Kennedy, and argued that only an insane person could prove the insanity defense. He was sentenced to death.