Recently a commenter talked about how she felt taken advantage of by a loved one who had schizoaffective disorder. This particular individual seemed to take a lot from his family and gave nothing in return. He refused to shower, help out around the house, pay for anything and would eat out at restaurants with no money and then insist his family come down to the restaurant and pay for him.

The person with schizoaffective disorder was being medically treated and the loved one felt that he was just manipulating the people around him.

Now, I can’t say what the motivation was in this scenario, but certainly, this commenter is not the only one to have found herself in that situation. So the question is, is mental illness an excuse for bad behaviour?

Understanding Mental Illness

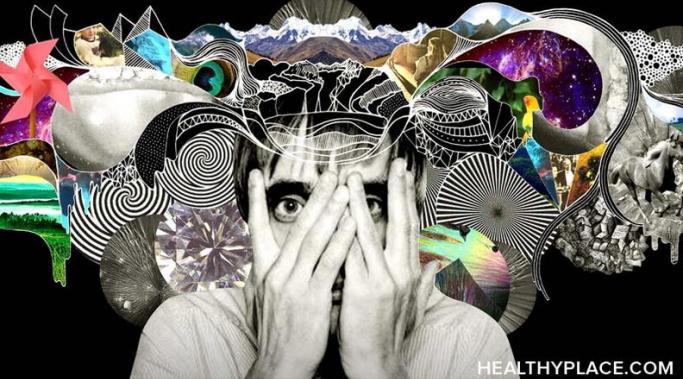

When people realize they have a mental illness like bipolar disorder or schizophrenia, one of the first feelings they have is fear. And there’s a lot to be afraid of. There are the treatment, doctors, symptoms, side effects and then there’s the illness itself. It’s completely reasonable to feel scared in that situation.

And in that moment, or possibly in a moment shortly thereafter, the fear of abandonment becomes a reality. A very reasonable and realistic fear is that people will abandon you because of the mental illness.

I have not done a book review on here but that’s because I don’t tend to read help books on bipolar disorder – I write that material, not read it. But recently one such book has landed in my possession and I’d like to take the time to recommend it: Loving Someone with Bipolar Disorder – Understanding and Helping Your Partner (second edition) by Julie A. Fast and John D. Preston, PsyD.

People often ask me how to help others with bipolar disorder and I believe this book could help partners answer that question.

This article is a continuation from Multi-Polar - The Many Moods of Bipolar Disorder part one.

Recently a reader asked me to describe the moods of bipolar disorder in my own words. OK, I thought, but a lot has been written (by me and others) about depression, mania and hypomania before. But then I thought about it and realized that there were actually many moods in bipolar disorder and just saying there are “up” and “down” moods sort of does a disservice to everyone struggling with bipolar disorder.

As I wrote, some people believe that if you don't have a mental illness, you can't understand someone with a mental illness. I'm not sure this is true.

I have been writing about mental illness for almost a decade now and part of the reason was to try and help people understand bipolar disorder and other mental illnesses. And I have succeeded in some regards. I get emails from people quite frequently that tell me how much more they understand about the disease now that they have read my writings. I am tremendously gratified by this.

But, of course, I reach a tiny percentage of people and the issue of mental illness stigma still affects us all. And some people, no matter how hard we try to explain ourselves to them, never seem to understand mental illness.

Which begs the question: can a person without a mental illness ever really understand what we’re going through?

One of the challenging things about being a person with a mental illness who talks about psychiatry (and doesn’t hate it) is that all those people who do hate psychiatry perk up and get mad. These people often identify as “antipsychiatrists” and I’m not their biggest fan. While I consider it quite reasonable to question your doctor, psychiatrist, treatment, therapist and other treatment aspects, I consider going after an entire branch of medicine ridiculous. There is no “antioncology” faction in spite of the fact that a large percentage of people with cancer die (depending on the type, of course).

And this manifests in many of our lives. It’s not that antipsychiatrists just attack me; it’s that people of that mindset attack your average person who is just trying to deal with a mental illness. It’s the people who say, “mental illness doesn’t really exist” or “psychiatric medicine doesn’t work” or many other things that many of us hear online and in our real lives all the time.

So how do you talk to these people who have decided that your disease doesn’t exist and you shouldn’t be in treatment?

Earlier this week I wrote a piece about being scared of trying antidepressants and as one commenter pointed out, there are increased risks associated with treating a person with bipolar with antidepressants. In fact, some would say that treating a bipolar person with antidepressants can worsen the course of the illness (always contraindicated as monotherapy and possibly undesirable altogether). Now, when I wrote the article I was only thinking of unipolar depressives, but, as one commenter pointed out, being diagnosed, correctly, with bipolar disorder, in itself, can be a challenge.

And this is absolutely true. Studies have found that it takes 5-10 years (from the time of the first episode) for a person with bipolar disorder to get an accurate diagnosis. There are many reasons for this, predominantly that people don’t get help when they have their first episode, but a major contributing factor is also misdiagnosis. People with bipolar disorder are often diagnosed with depression or schizophrenia first and this can have devastating outcomes.

For some reason people like to come on here and tell me (and sometimes others) that I’m not bipolar. They feel, for whatever reason, that my writing is not that of a person with bipolar and somehow it indicates that I’m not bipolar. I’m not expressing the right emotions. I’m not writing whatever it is that a “real” bipolar person would be writing.

And this happens in real life too. People somehow feel qualified to determine a person’s mental status simply by the way a person with bipolar acts in front of them.

Well, for the record, I would like to say from me, and all the other mentally ill people in the world: bite me (or, you know, us).

![MP900321083[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2012/06/MP9003210831.jpg?itok=qIqD0HL6)

![MP900285007[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2012/06/MP9002850071.jpg?itok=jA3ISj4_)