Recently I heard a familiar story from someone struggling to understand her dissociative disorder but unable to get any direct answers or explanations from her therapist, who is exercising caution because she doesn't want to reinforce the dissociation. While this is an understandable and common concern for clinicians treating Dissociative Identity Disorder, there is a vast difference between psychoeducation and fostering further fragmentation. When you refuse to fully invest in the former you leave your clients ripe for the latter. If for no other reason than that, Dissociative Identity Disorder treatment must include psychoeducation.

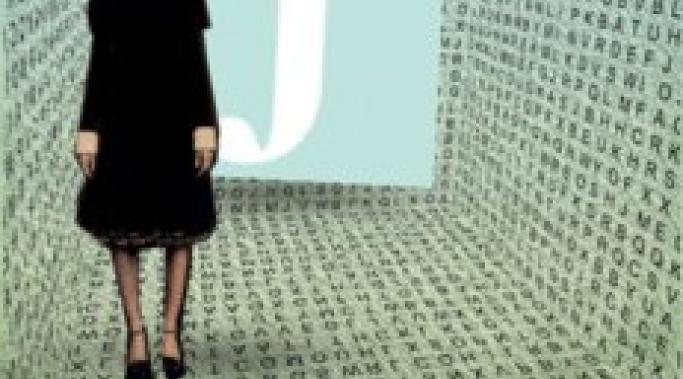

Dissociative Living

Dissociative Identity Disorder is caused not just by trauma, but a number of factors that come together at just the right times, in just the right places, over and over again. I’ve discussed in some depth the factors that I believe contributed to my development of DID. But those factors might be different for you. Furthermore, each contributing factor carries its own weight. In other words, the causes of Dissociative Identity Disorder are unique to each person in both definition and size.

Decreasing dissociation in dissociative identity disorder (DID) relies on actively increasing awareness of the world around us. Dissociation is the process by which we separate ourselves from our experiences, memories, bodies, and very selves. When we're dissociating, we're disengaged from some or all of our own reality.

It's not inherently a bad thing; I truly believe dissociation serves a valuable purpose, and not just in traumatic circumstances. But there's no doubt that the chronic, severe dissociation intrinsic to dissociative identity disorder is problematic, disruptive, even at times actively destructive. By increasing awareness, by being more fully present in our bodies and minds, we can mitigate the damaging effects of dissociation.

While not everyone with Dissociative Identity Disorder also has a diagnosable depressive disorder, I’d wager at least 50% live regularly with some type of depression. As for me, I have Major Depression and Dysthymia. The former is a real pain; the latter is far more manageable. I’ve never taken either one very seriously and I think the magnetic relationship between dissociation and depression is the primary reason why.

While not everyone with dissociative identity disorder also has a depressive disorder, I’d wager at least 50% live regularly with some type of depression. As for me, I have major depression and dysthymia. The former is a real pain; the latter is far more manageable. I’ve never taken either one very seriously and I think the magnetic relationship between dissociation and depression is the primary reason why.

When I was in college I confided in a friend about an incident at a party that left me feeling taken advantage of. Initially I was taken aback by her outrage on my behalf. A few days later, I was equally shocked by her hostility towards me. It took many years before I understood that Dissociative Identity Disorder played such a large role in the party incident that I came away with an impression of it that wasn't accurate at all. By reporting it to my friend, I essentially told a lie, though I didn't realize it at the time. Today her wildly varying reactions make sense to me because I have a much better understanding of the potential pitfalls of my dissociative memory.

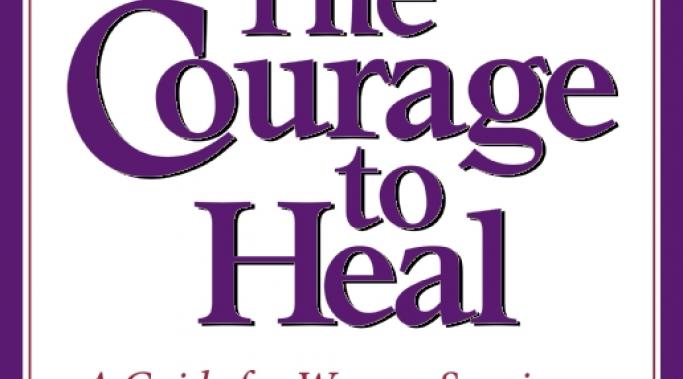

The Courage to Heal is a self-help book – “A Guide for Women Survivors of Child Sexual Abuse” - that has enjoyed widespread popularity among both those living with Dissociative Identity Disorder and many of their treatment providers since its first publication in 1988. I first read it six years ago and found it helpful in some ways. But subsequent readings have illuminated for me the book’s biggest flaw: its reckless approach to traumatic memory.

How many times have those of you with Dissociative Identity Disorder drawn a boundary of some kind and later felt awash in guilt and anxiety? If you're like me, the answer is "just slightly less than always." And it's not just those of us with DID that struggle with boundary setting. That backlash of guilt and anxiety isn't unique to Dissociative Identity Disorder. But I suspect the path to resolving it might be.

I write about Dissociative Identity Disorder in part because I'm disturbed by the sheer volume of false and misleading information about DID. It bothers me that an overwhelming number of online resources are teeming with misconceptions so profound that the end result is a definition of the disorder that further shrouds it in mystery and controversy. Not to mention the fact that nobody seems able to explain it without relying on a misnomer, Multiple Personality Disorder, to do so. It took me a long time to wade through all the jargon and arrive at a definition of Dissociative Identity Disorder that accurately explains my experience of it.

Managing the self-sabotaging behaviors that make life with Dissociative Identity Disorder so difficult doesn't mean getting rid of them. It means learning to live with them; recognizing and investing in the opportunities for growth inherent in self-sabotage. For me, that requires (1) acceptance of those behaviors, no matter how repugnant, (2) honest communication devoid of the power struggle that characterizes instinctual responses to self-sabotage, and (3) welcoming compromises that allow me to keep moving. When I discovered an alter was blocking internal communication, I was surprised to learn that all three of those things are possible. But it was the compromise that amazed me the most, and ultimately changed my life.