I’ve been working on coming up with mission and vision statements for a charity I work with, and one of the things that a fellow board member said was that we want to end self-discrimination. I thought this was quite brilliant, and, of course, quite true. One of the things people with a mental illness face isn’t just discrimination from others but discrimination and stigma from themselves. And if we want to fight discrimination and stigma in the world, this begins by looking in the mirror.

How Others See Bipolar

Being sick, I think with anything, can be extremely isolating. Being sick, you’re not “like everyone else.” Be it cancer, HIV, diabetes or bipolar disorder, there is a moment when you realize that you’re different and that difference is isolating.

This is a form of internal isolation. But, of course, isolation can be external every bit as much as it can be internal. And sadly, most people with bipolar disorder experience heaps of both.

Many people with bipolar disorder hold down jobs, just like everyone else. We get up, swear in traffic, survive on coffee and rant about our bosses behind their backs.

But people with bipolar disorder or another mental illness have special challenges when it comes to work. We’re sick more often, we need time off for medical appointments and stress affects us more than your average person. Here are a few tips on handling work and bipolar disorder.

I have had a lot of bad bipolar days in my life. Days when I was incapacitated. Days when I couldn’t make food for myself. Days when I couldn’t work. Days when I couldn’t talk to anyone. Days when I just couldn’t function.

On these days, I’m sick. And in some regards, it’s a type of sickness that is like many others. I feel like trash, I don’t want to move from the couch and everything hurts – that could describe a cold or the flu as well. But as it happens, it also described a bad day for depression or bipolar disorder.

But here’s the thing, when someone calls and asks if I want to have coffee, saying I’m too depressed isn’t seen as acceptable. That’s seen as weakness. That’s seen as something wrong with me. Whereas, if I said I was sick with a cold, that would be alright, because, after all, everyone gets colds and when they get them, it’s okay not to feel like socializing.

And I can’t tell you the number of days I’ve said I was sick with the flu, or a cold, or a stomach bug or anything but sick with bipolar. But really, that’s what I am.

Even amongst people with bipolar disorder, the disorder is highly contested. People argue about what it’s “really” like to have bipolar disorder. What mania is like. What depression is like. And perhaps most hotly debated of all is what the appropriate treatment of the symptoms is – antipsychotics, mood stabilizers, antidepressants, psychotherapies, alternative treatments and so on. People argue about virtually everything.

And one of the reasons why this is the case is because the experience of bipolar disorder is so vastly different. Some people experience manic psychosis, others do not. Some people experience delusional depression, others do not. Some people experience suicidality, others do not. And so on. Severity varies as do symptoms.

And I would argue that much of this disagreement stems from the two basic types of bipolar disorder: well-controlled and not well-controlled bipolar disorder.

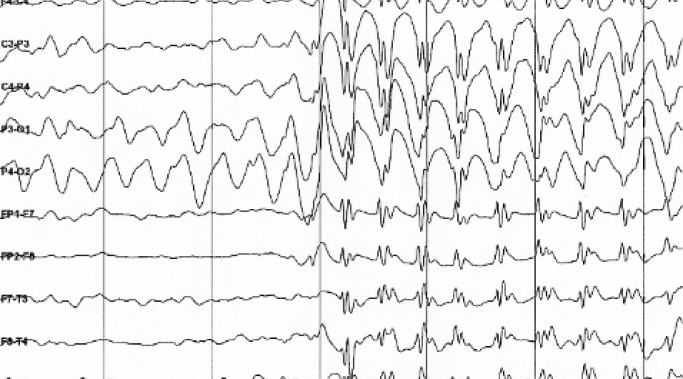

Recently, it was announced that the very first diagnostic brain scan for a mental illness became Food and Drug Administration-approved. This test uses electroencephalography (EEG) to diagnose attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD). Finally, people with a mental illness (in this case ADHD) can point to a biological test and say, look – see – my disorder is biological in nature and we can test for it.

It’s not terribly surprising that ADHD is the first disorder to have this type of test as we understand an ADHD brain better than we understand a brain with other disorders. Nevertheless, it won’t be the last. Scientists are actively working on diagnostic tests for depression, autism, bipolar and schizophrenia too.

And while I consider this a major breakthrough in our real, tangible understanding of mental illness, there are reasons why diagnosis by brain scans matters and reasons why it doesn’t.

While it seems hard to believe, some people want others to stay mentally ill and, indeed, sometimes even individuals themselves, choosing to maintain mental unwellness. You have the obvious example of people refusing medication and thus becoming very sick but there are other forces as well that can encourage a person to stay acutely, mentally ill.

Bipolar moods vary in duration by person but typically, an untreated bipolar mood can last months or even years. All a bipolar disorder diagnosis requires is the presence of one manic/hypomanic mood episode and one depressed mood episode. This means that a person could be in a year-long depression and have only experienced one week of mania, a year ago, and still qualify for a bipolar diagnosis.

This is much to the surprise of many as there is a pervasive belief that bipolar disorder is about frequent “mood swings.” However, simply “being moody” is not indicative of bipolar disorder.

Bipolar disorder is a scary illness, but sometimes even scarier is the idea of treatment. Logically, going to the doctor, getting a diagnosis and getting help doesn’t sound scary, but if you’re the one faced with psychiatrists, personal, probing questions, destroying what you know and treatments that might make you feel worse before you feel better, you might find the concept daunting.

But what do you do if you’re a loved one of a person with bipolar (or another mental illness) who is refusing treatment?

I first started receiving psychiatric treatment when I was 20 years old. At that time, I was pretty separated and not very attached to my parents. Nevertheless, they and their opinions did have an impact on me. And when I told my mother I had bipolar disorder her reaction was akin to not believing me. She was entirely ignorant about mental illness (and to be fair, I had been too) and mental illness treatment.

She, naturally, wanted me to treat this problem with herbs and other nonsense. And in spite of the fact that I was detached from this woman, her lack of support affected me. At the time, all my energy was being used to fight bipolar disorder, and now I had to fight her too. It was kicking me while I was down. Way, way down. And while she didn’t see it that way, I can attest to the fact that it sure as heck felt that way.

But luckily for me, I was not under her care. Luckily, even though she eventually pressured me into trying out alternative nonsense, I still got the real, medical help I needed. Had I have been younger, this might not have been the case.

And unfortunately, some youth are in this position right now. Some youths feel they have a mental illness and are in the charge of their parents’. And some youths have even told their parents that only to be met with a wall of disbelief or told they’re “overly dramatic.”

I feel for these youths. They’re in a really tough spot. But there are things youths can do even if a parent doesn’t believe their son or daughter has a mental illness and refuses to support their desire to get help.

![MC900441394[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2013/08/MC9004413941.png?itok=UHwwmyXi)

![MP900405644[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2013/06/MP9004056441-1024x685.jpg?itok=sLTFbNTj)