I remember, before trying medication, I was terrified of it. I had the same misconceptions that many people do:

Medication is for weak people

Antidepressants are just “happy drugs” designed for people who can’t handle life

Medication will ruin your brain

Doctors give out antidepressants like candy whether you need them or not

As it turns out, none of these things are true, but they sure seemed true at the time.

So I get fear of antidepressants and other medication. Psych medication is scary stuff.

But sometimes you have to face that fear in order to get better.

Bipolar Treatment – Breaking Bipolar

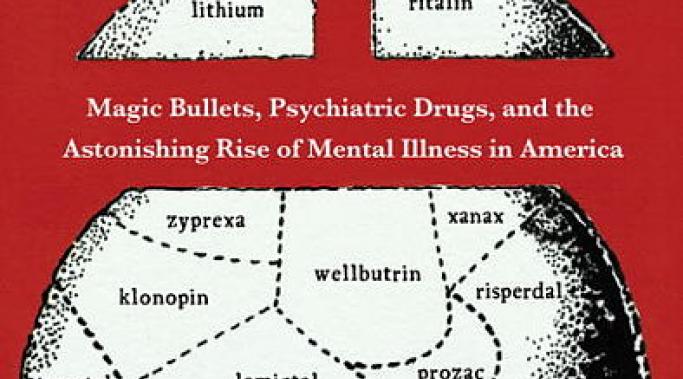

Many people here have read Robert Whitaker’s Anatomy of an Epidemic: Magic Bullets, Psychiatric Drugs, and the Astonishing Rise of Mental Illness in America (New York: Crown Publishers). And some of these people will likely claim that the book changed their lives or, at the very least, their view of psychiatry and psychiatric medication.

Well. Ho there. You would think with such a ground-breaking book I would be all over it.

Guess again.

I refuse to read Anatomy of an Epidemic. And yes, some people will fault me for this. But I have a good reason. I refuse to read Anatomy of an Epidemic as I have no desire to be outraged at a misunderstanding of science for 416 pages.

The Poster Child: Robert Whitaker

Robert Whitaker is the poster-child for antipsychiatry, which is his prerogative. If he enjoys talking to throngs of antipsychiatrists then I say, better him than me.

And part of his criticism of psychiatry is well-deserved. I would say that being concerned with the use, and possibly overuse, of some medications and the prescribing of heavy psychotropic medications to children is quite warranted. I take no issue with the fact that debate and concern is appropriate here.

What I do take concern with is his contention that psychiatric medication actually worsens treatment outcomes and causes disability. This is the reason why antipsychiatrits love him and it’s the reason I probably couldn’t stand to be in the same room as him.

I once wrote a post called, My Bipolar Symptoms Aren't Your Symptoms: I'm More Bipolar Than You. The point of the post is that two people can experience bipolar disorder very differently. Even when two people meet the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM) diagnostic criteria for bipolar disorder, their individual list of symptoms can be quite different. One might be expansive when manic, the other might be irritable. One might sleep too much when depressed, the other might sleep too little. And so on and so forth. Neither one of them is the “right” kind of bipolar and neither one of them is “more” bipolar, they are simply suffering from the same illness differently.

Similarly, treatments are also individual. What works for one person simply doesn’t work for another. And that’s OK.

In my last post I talked about what it is to be an e-patient. These are the people who are engaged in their own healthcare - they are empowered patients. But if your relationship with your doctor is more passive, how do you become empowered?

Have you heard of the e-patient? If not, it’s OK, I hadn’t heard of them up until about a year ago either. And quite frankly, once I did hear the term, no one really explained it to me so I figured it was an “electronic” patient – maybe one who walked around with their health records on a USB stick, or maybe a cyborg patient (in which case, I qualify).

Well, it turns out that there aren’t a lot of cyborg patients and while an e-patient might walk around with their medical records, “e-patient” actually refers to patients who are equipped, enabled, empowered and engaged. And, depending on whom you ask, also educated, expressive, expert and electronic.

That’s a lot of stuff. And quite frankly, way too much pressure, so let’s boil it down – an e-patient is one who’s engaged with their own healthcare, and ideally, we all should be one.

If you’ve been poking around for mental health information for a while you’ve probably seen them: The people who decry psychiatry and all associated therapies. These people come in various shapes and forms but they often call themselves “psychiatric survivors” or “antipsychiatrists.” These are people who claim that psychiatry is evil and psychiatrists are nothing but abusers. These are people that claim that psychiatric medication will cook your brain and that those who use psychiatric services have simply been duped into believing the lies of “big pharma.”

It should surprise no one that I’m not a fan of these people. In my opinion, these people prevent sick people from getting the help they so badly need and they can cost someone their life.

And writing off psychiatry as a field of medicine reminds of refusing to eat Chinese food.

There is an interesting, if perhaps disturbing, phenomenon in psychopharmacological drug treatment. It is the instance where a person initially has a satisfactory response to a medication, getting well, and perhaps staying well for years, only to have the illness come back at a random time in the future. The medication just “stopped” working. We have known about this for a long time with many drugs including antidepressants and anticonvulsants (mood stabilizers) and it’s sometimes referred to as antidepressant “poop-out” (I kid you not).

But this phenomenon goes against even the most basic understanding of medication, so why is it happening?

Recently, I was talking with someone on Twitter and she was concerned about the side effects of psychiatric medication X. I asked her what her starting dose was for the psych medication and she said 15 mg. Now, I’m not a doctor, but I can tell you two things:

That is ridiculous.

That will certainly make the patient stop the medication early due to side effects and never even find out if it works.

On Twitter a follower asked me about a specific side effect of a medication. She was considering taking the medication and was worried she might suffer from this side effect. This is a reasonable concern and it’s good that she’s researching the drug's effects and possible problems ahead of time.

But the thing is, while knowing about the possibilities is good, worrying about the possibilities is pretty useless. You won’t know if you will get the side effect unless you actually try the drug. The only way to know what is going to happen is to roll the dice.

Mental health is something that matters whether you’re seven, seventeen and seventy, and any of those ages can fall victim to a mental illness. Depression, for example, is quite prevalent and undertreated in the elderly.

But if you’re underage, it may be more difficult than just going to your doctor to start the process of getting help for your mental health. It likely means explaining your mental health concerns to your parents; which, quite reasonably, is scary to a young person. (It’s scary to an old person too, but I digress.)

So how do you tell your parents you think you need mental health help?

![MP900255362[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2012/06/MP9002553621.jpg?itok=ccR4teIZ)

![MP900386199[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2012/05/MP9003861991.jpg?itok=UjPcJoRw)

![MP900227837[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2012/05/MP9002278371-124x180.jpg?itok=xgyGSOGl)

![MP910221009[1]](/sites/default/files/styles/blog_listing/public/uploads/2012/04/MP9102210091-1024x682.jpg?itok=f95zPNhK)